Marylou Simpson in 1950s Sun Valley

Photo by Penny Converse, photo colorized by Vickey Hanson - Mountain

Dreamworks.

Seventy Years of Sun, Snow and Stories

In honor of Sun Valley Resort’s 70th birthday, longtime resident and Idaho Mountain Express columnist Betty Bell records the reflections of some of its “children.”

When I sat down to begin this reminiscence, I looked for a handle, something to latch onto. Did I see Sun Valley as an “It?” Or a “Place?” Or as “Us?” What worked was “edifice,” and I’ll use it as a metaphor, even though I bet it loses integrity along the way. With edifice I got a clear picture of cornerstones, solid things to dust off, look at closely and read the names inscribed. The following characters were part of Sun Valley’s post-war history, occupying it roughly from the late ’40s to the early ’50s.

Then and

now: Betty Bell, top, in her airborne racing days. Today, weaving

her magic words in her corner at the Idaho Mountain Express office in

Ketchum.

Then and

now: Betty Bell, top, in her airborne racing days. Today, weaving

her magic words in her corner at the Idaho Mountain Express office in

Ketchum.

General Manager W.P.

“Pappy” Rogers—a big man in every way, fiery but warm, demanding but

appreciative, wholly hands-on always, a greeter of nearly every incoming

bus and the rider of many a Shoshone-bound bus when it snaked its way

through the snowplowed canyon the highway often became. Abundant

snowfalls were common then.

Florence “Flo” Law, executive assistant. Most of us

suspected she was co-general manager, the lady who could smooth

everything out. For example, when Mr.Rogers’ softball team would get

whumped by Nedder’s team, my future husband’s team (Ned Bell was manager

of the employees’ cafeteria as well as the famous BoilerRoom), Mr.

Rogers would find him even though Ned had put some effort into not being

a highly visible target. Mr.Rogers would summarily fire him, tell him to

get to Personnel and pick up his train ticket back to York, Nebraska—and

“don’t miss that five o’clock bus to Shoshone!” But after an hour or two

of cooling-off time that likely included a chat with Mrs. Law, he’d seek

out Ned again, de-fire him, and tell him never mind about the bus.

Eddie Seagle, chief engineer. The man who made things work down here in

the valley and up on the mountain, and a man of many skills. In a time

of barely intermittent radio—forget TV—every blue-sky, aspen-gold fall,

he’d spool out a par five’s worth of wire in and around the Opera House

and splice them magically to pull in a silken voiced sportscaster who—to

a captivated audience ranging from bellhop to the big man

himself—artfully chanted the World Series play by play. I never saw

games with more clarity than those.

Dr. John Moritz, pioneer bone man. In a time of novel new ways to break

a leg, Dr. Moritz was a national innovator of procedures, plus being an

all-round physician —deliverer of my first two children in the wing on

the third floor of the Lodge that served as a hospital until a real one

was built. So beloved and respected was Dr. Moritz that we gave our new

hospital his name.

Bald Mountain has to be acknowledged here…dear Baldy, our Accessory

Dwelling Unit, our immovable, incomparable force.

I arrived in 1946, early enough to be linked to the

cornerstones—a flatlander come from Nebraska to learn to ski. There’s a

major chunk of time when I lost touch entirely with the world beyond, a

long run of focusing on getting to the mountain and riding free up the

three single-chair lifts—River Run, Exhibition and Ridge, and I was smug

if not snug in my hot-gear garb of three sweaters under a nylon shell. I

survived those rides by cocooning in the big, canvas-wool-lined cape

that lift attendants draped across every skier’s shoulders. When I skied

off on top I’d be warm again, ready for more play in the snow, ready to

bag as many as I could of the elusive nano-seconds of bliss and

perfection.

My first summer in Sun Valley, the one that hadn’t

been a part of my plan, I discovered that hiking wasn’t necessarily

horizontal, and that I could always do it in a National Geographic

setting…I discovered that golf was a new game to play but a hard thing

to learn on nine skinny fairways. Luckily there were plenty of hit-once-and-lost-forever Titleists sliced into the big-time rough to

offer free pickings and make the twenty-dollar season pass seem not too

steep. I stayed several summers to be positioned for winter before it

sank in that I was home.

Four fellow “first coursers” shared the tales that follow. Just between

us, I was taken aback to see how much they’ve aged. As young things,

we’d all linked up to the cornerstones about the same time and jointly

raised our kids who’ve had kids who’re raising kids now linked.

On this its …us …our—seventieth

birthday, I think it’s OK to say ‘Happy birthday, Mom.’

Then and now: Marylou Simpson, still smiling. Her husband, Jack, passed away in 2000.

It was a standard

address to the troops: “If you live here, you ski. Get on that mountain.

You have to be able to talk to guests about skiing.”

Marylou Simpson can’t pinpoint the first time she heard Mr. Rogers, the

general manager, preach this sermon, and since she was already a skier,

she embraced it as gospel.

Unlike many employees who hailed from Union Pacific headquarters in

Omaha, Marylou wasn’t a flatlander. The train she arrived on in Shoshone

hadn’t come from Omaha, and she didn’t have the railroad pass that was

part of the package for employees. She didn’t even have a job. When she

and two good friends stepped off into that hot first day of July in

1946, they had stubs for one-way tickets from Seattle—$20 each, coach.

“It was so flat…so dusty. I said, ‘What have we got ourselves into?’ But

then we got on the bus, and when we came down Timmerman Hill and saw the

mountains, I knew this was where I wanted to be.” The girls came to Sun

Valley at the urging of Jack Simpson, a young sailor on leave they’d met

in Seattle. Jack’s family had settled in Ketchum long before Mr.

Harriman discovered it. Owen, Jack’s father, owned what had first been

the Lewis/Lemon Grocery Store before becoming Simpson’s Grocery—a grand

old building that then morphed into the Golden Rule grocery store before

morphing through short-lived morphs I’ve forgotten into its present

reincarnation—Iconoclast Books. Before the war, Jack’s job had been to

drive the store’s truck over Galena Summit on the “wagon trail” and

deliver groceries in Stanley and Clayton.

Through Jack, that first summer, the girls found jobs as cocktail

waitresses in another of Owen’s enterprises, the Sawtooth Club. The

ladies were a big hit.

“There wasn’t a single gal in town,” Marylou said.

“The Navy, when it cleared out of Sun Valley, corralled them all.”

One of Marylou’s first Sun Valley jobs was at the

warming hut on top of Baldy, where she was cashier.

“I was the only one they’d let ski down with the money after work,” she

said. Most employees, though eager to follow Mr. Rogers’ commandment,

were still bunnies not to be counted on to get down the mountain with

the money sack intact.

Surprise: Marylou married Jack. Jack, who died in 2000, was instrumental

in launching the Sun Valley junior ski racing program that’s so solid

today, and through the years the Simpsons and their sons Mike and Pat

were entwined in Sun Valley’s ski history—Pat once won the National

Junior Championships.

When Jack was 16, he skied for Sonja Henie in the movie Sun Valley

Serenade. He skied all of the spectacular runs and cartwheeled through

all of the spectacular crashes—but at the end of every crash the camera

clicked off and didn’t click on again until it was back on a Hollywood

set and zeroed in on Miss Henie wiping ersatz snow from her face. She

never set foot in Sun Valley, poor thing—and Jack never shook his

nickname—“Sonja.”

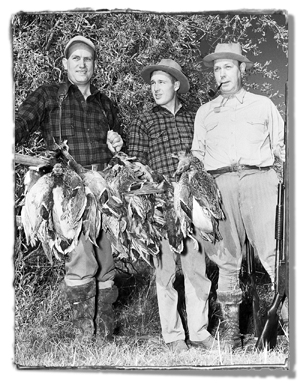

Then and now: Clayton Stewart, top center, hunted and fished with a myriad of Hollywood celebrities. Today, he is happy to fish in solitude along the Big Wood River.

It’s not likely you’d

be looking for Clayton Stewart to serve him a subpoena, but should you

be, you’d find him in Atkinsons’ Market in Ketchum, about nine on most

mornings. He’d be sitting at one of the small front tables, back-lit by

the sun with his hand around a cup of coffee. I didn’t have a subpoena;

he’d agreed to chat when I found him there. I said, “Hi Clayton,” and he

looked up and turned loose a gentle, slow-motion smile that spread clear

across his face, and I thought, “I remember that smile… .”

Clayton, an Idahoan, graduated from Shoshone High School in 1937 and

came directly to Sun Valley. He already had a job—as a fishing guide. He

was 16.

“Did you guide any celebrities?” I asked, not commenting about his

tender age. “Well…I took Gary Cooper fishing that summer…then in ’38

Hemingway was here, and I was his hunting guide. I did a lot of guiding

for Hemingway—he loved to kill things—I didn’t know there were people

who just like to kill things, but there are.”

Along with a few million others, I’ve fixed Hemingway close to the top

of my favorite authors, so when Clayton got even more specific I

interrupted. “Did you guide any other celebrities?”

“Oh yeah…what’s his name? You know…the guy with the big ears?” We sat

there stewing a bit as is the wont of those of us advanced in

far-ranging wisdom but challenged if we have to summon a specific name

from our vast collections. Surprisingly, a name did float out—“Clark

Gable?”

“Yep. That’s the one—I did a lot of fishing with Clark Gable.”

Clayton’s resume lists more than traipsing around country he loved and

getting paid for it. In the early ’40s he managed the State Liquor

Department in Sun Valley. “You mean the liquor store?”… “No, the State

Liquor Department,” he corrected. “Nobody drank anything but bourbon and

gin until guests started coming from back East—and they had a taste for

vodka and such. And wine—we didn’t know anything about wine, so Sun

Valley brought in a wine steward from Austria, Peter Riehl, I think it

was, and they built a wine vault in the Lodge basement—buried it

there—and then they made darn sure to hide the key so employees—most of

them teenagers, couldn’t get hold of it.”

In his stint as transportation manager, it wasn’t only getting guests in

and out of the valley he had to worry about, “There was all that

laundry.”

“Laundry?”

“Yeah—we had to ship out all the linen to UP headquarters in Pocatello

and get it done there…we’d get it all separated—sheets, pillowcases,

towels, all that stuff. Sometimes we’d fill up a couple cars.” Railroad

cars, he clarified—not Subarus.

Clayton, 89 now, still lives in Ketchum. Once in a while on a fine

summer day when it’s too busy here, he drives south to familiar and

cherished country around Hagerman. He doesn’t take a rod or gun with him

these days, nor do I imagine that he hankers to—he’s already lived the

best of it.

Then and

now: Petra Morrison relaxes atop a rock at Alturas Lake, and atop a

knoll overlooking her family’s

Then and

now: Petra Morrison relaxes atop a rock at Alturas Lake, and atop a

knoll overlooking her family’s

former property.

I’ve had a few

titles, but never “shrinking violet.” So when I called Petra and said

I’d like to hear a

couple of recollections from her early days in Sun Valley, I wasn’t put

off when she tried to steer me away: “You should talk to Earl McCoy—he

was one of our best early skiers—he won that Diamond Sun race straight

down Baldy.”

“Well, I’d really like to talk to you.”

“And Gladys McAtee—Val McAtee’s widow. Val, worked for Sun Valley for a

lot of years, and Gladys has wonderful stories—she’s in her nineties

now, but really sharp.”

“Uh huh—but I’d really like to talk to you.”

And Petra, the same courteous woman I remember from the late ’40s when

she worked in Sun Valley’s personnel department, gave in, and invited me

to her place—which is what I’d been angling for all along. I’d been to

Petra’s home once before, and I was curious to see if I’d still think

she sits atop the best piece of real estate in all of the Wood River

Valley. I do. She does.

Petra’s piece of real estate, where she lived with her husband, Frank,

until he died in 1994, is a roomy knoll on the north side of Weyakkin—earlier

that whole spread had been the Farnlun Place, owned by Petra’s

grandparents, who came to Ketchum in 1895. Just after you drive into

Weyakkin, a road on the left still signed Farnlun Place winds gradually

up and around to Petra’s knoll, and the panorama there swings from

beyond Hailey south to beyond Galena north.

At the dining room table with a window-wall featuring Baldy, I asked

Petra what it was like when construction started in Sun Valley. “Oh, it

was a big impact right away. I was going to a two-story brick school in

the middle of the block where Giacobbi Square is now. School was just

two rooms downstairs—upstairs was the gym. When construction started and

families began to move in, right away school became four rooms—and with

four teachers, too!”

“Was there friction with all the new kids?”

“No, no. Right away, we were close. They fit right in.

“There weren’t many buildings that first winter, and all the

construction workers lived in tents—they built them on platforms with

kind of walled sides and they had stoves in there—whole families lived

in tents. I was shocked—our house was small, but it had electricity—but

not indoor plumbing—and it sure seemed like a castle alongside those

tents.”

I asked Petra to tell me about one memorable “little thing.” “Well,” she

said, “the Personnel Department was right down the hall from Mr. Rogers’

office, and if it was getting close to Christmas and we still didn’t

have any snow or not enough, Mr. Rogers would come stomping down the

hall and just boom out, ‘Everybody get on over to church—pray for snow!

We need snow!’

“And I’d think, ‘Really… .’ But the

funny thing was, it always seemed to work.”