| click here for the |

| front page |

| features |

| proctor,ruud+dollar |

| beyond boarding |

| bell,odmark+puchner |

| trinity springs water |

| arts |

| black+white photos |

| jack burgess |

| r.l. rowsey |

| living |

| yoga |

| decorative concrete |

| recreation |

| vO2 workouts |

| snowshoeing |

| dining |

| scotch |

| stews |

| calendar |

| winter 2003-2004 |

| to-do |

| sun valley essentials |

| listings |

| galleries |

| dining |

| fitness |

| equipment rentals |

| outfitters + guides |

| lodging |

| maps |

| ketchum + sun valley |

| local art galleries |

| the guide |

| last summer |

| advertising |

| about us |

| copyright |

|

Copyright

© 2003 Express Publishing Inc. All Rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form or medium without express written permission of Express Publishing Inc. is strictly prohibited. |

|

Produced

& Maintained by Express Publishing, Box 1013, Ketchum, ID 83340-1013 208.726.0719 Voice 208.726.2329 Fax info@svguide.com |

|

The

Sun Valley Guide is distributed free twice yearly to

residents and guests throughout the Sun Valley, Idaho resort area

communities.

Subscribers to the Idaho Mountain Express will receive the Sun Valley Guide inserted into the paid edition of the newspaper. |

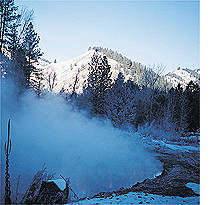

photo by Kirk Anderson

water from

another time

by Matt Furber

Trinity water chief scientist Roy Johnson understands the Bavarian tradition of “Fruhschopen,” enjoying a morning beer, often before Sunday Mass. It is a pure experience.

The pleasure is probably older than the German beer purity law of 1516 called the “Reinheitsgebot.” As the oldest consumer protection law still enforced, the promise of quality is as sure as the water percolating from the earth 100 yards from Johnson’s office by the South Fork of the Boise River in southcentral Idaho near the Trinity Mountains, 40 miles west of Ketchum.

Driving out to see one of the masters of bottled water, there is a dusting on the mountains from the first snow of the season. The autumnal equinox is a week away. It is hard to think of any of those delicate fresh molecules making it through the day much less 16,000 years, which is what Johnson and all the Trinity Springs literature and labels list as the “born on date” for their product.

It is difficult to grasp the significance of capturing such old droplets of water in a bottle quickly to stave off the inevitable: The molecules bubbling out onto earth’s surface are soon exposed to contaminates that exist everywhere outside the depths of the earth. Once jettisoned to the surface, the water leaves the safe confines of a protected aquifer and its days of purity are numbered.

photo by

Kirk Anderson

Johnson, a Chicago native, enjoyed his share of Bavarian toasting during his time as a veterinary student in Munich, Germany. With the kind of history and understanding he has about high quality beverages, investing his time and energy in a cosmopolitan Bavarian beer company might have made more sense than studying water streaming slowly out of a hole in a rock in rural Idaho. But blood is thicker than water, and Johnson’s brother Mark is one of the three founders of the small bottled water company that got its start hand delivering water in Sun Valley.

The chief scientist’s

rock in question is the 23,000 square mile Idaho Batholith, a 20-mile

deep impermeable granite barrier protecting water reserves from

impurities of the outside world. The hole is a spring that reaches 2.2

miles through faults in the batholith—Greek for deep rock—providing an

outlet for the 16,000-year-old water. It is water from the end of the

last ice age.

If the Jeb Clampett family could make it with bubbling crude, perhaps

three entrepreneurs scratching their heads around a spring of crystal

clear water could make it, too.

Arriving by car, one finds that the source of this remarkable water hardly requires a walk. A few springs are near a road, says Johnson, who explains that transportation is part of the combination that will make Trinity successful. Water is heavy and to make the business viable, it is necessary to get the water to market as easily as possible.

Bubbling up after 16 millennia at a rate of 250 gallons per minute, the precious uncontaminated resource is quickly bottled, boxed and loaded into semi-trailers to be hauled off to market.

Mark Johnson began his journey to Trinity, which is between Pine and Featherville, with an interest in clean water for raising organic plants for a botanical extraction business. He met the other two founding partners, Stan Acker and Sun Valley native Jock Bell, at an archeo-astronomy seminar in the fall of 1989. The trio got off the ground in December 1990, after Acker found Johnson’s clean water and Bell’s family discovered the land around the source was for sale. Bell has had a lifelong passion for geology and natural water sources, which has translated into a hometown venture close to his roots. Exploiting the Trinity springs for their good drinking water potential became the focus of their venture rather than organic plant irrigation.

In the beginning, landslides along the previously unimproved road to civilization and snow in winter made the hand delivery by Johnson and Bell to Sun Valley a real chore. Sometimes they pulled their deliveries out by sled.

More than a decade later the Johnson brothers (Mark eventually could afford to hire his brother), Bell, a staff of 24 and at least 140 investors have pulled a product straight from the earth that could one day prove more precious than oil. At least half the investors live in the Wood River Valley surrounding Sun Valley.

The spring water comes out of the ground at about 138 degrees Fahrenheit, an excellent temperature for soaking, but today the focus for Idaho investors is to keep improving national distribution of its bottled water product.

Soaking is not entirely out of the picture, however. Enjoying the source of Trinity’s bounty entails more than a trip to the grocery store.

Untapped, Trinity water bubbles from three natural hot springs to steam in pools at 138 degrees Fahrenheit. The home of the source in south central Idaho is at the foot of the Trinity Mountains and very near the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. photo by Kirk Anderson

The company controls three springs, another reason for the name Trinity. The springs, clustered together on about 50 protective acres, are called Landa, Paradise and Bridge springs. Only the Landa spring is currently tapped for bottled water. Just up the road, the company owns a group of cabins and a lodge adjacent to the Paradise hot spring, which is essentially an Olympic-sized pool. Hot water seeps from the granite bed of the pool mixing to a temperature that is comfortable for hours.

The water is smooth, and the hot seeps offer a hint of what lies within the rock bed.

The third spring, Bridge spring, flows into undeveloped pools downriver below Landa. They are more public, says Roy. It is a hot spring for travelers just pulling off the road for a quick dip. Guests are welcome to visit the springs or enjoy the cabins when they soak in either location. As the company enjoys more success from its water sales, improvements continue to be made.

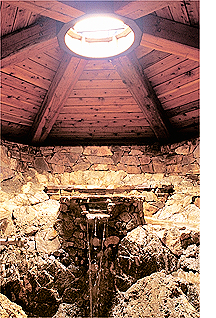

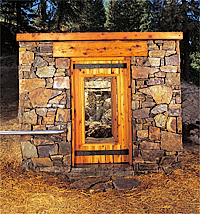

In the mid-90s the team built a beautiful stone springhouse designed to protect the steady water source from contaminants. The idea was to welcome the water into a familiar environment, says marketing director Sharon Egan.

A round glass window guards the opening with a rubber seal not unlike a ship’s portal. When in production, water flows by gravity into the adjacent straw-bale, stucco-sided bottling barn, which is also a new building. The ruddy exterior reflects the company’s earthy beginnings, which included investment from the environmental activism branch of the Grateful Dead, the Rainforest Action Network. A great deal of support also came from the Johnsons’ father, Bill, during some of the tough times. Bill Johnson was also one of the original investors.

Built

of hand hewn rock for protection, the building surrounding the Trinity

spring was also designed to honor the source, allowing the water to

emerge from the ground into a familiar environment.

photo by

Built

of hand hewn rock for protection, the building surrounding the Trinity

spring was also designed to honor the source, allowing the water to

emerge from the ground into a familiar environment.

photo by

Kirk Anderson

All three springs have identical constituents and provide a consistent flow of the same temperature water. From the state of Idaho, Trinity has a permit to appropriate about 265 million gallons of water per year, which is equivalent to one cubic foot per second or 400 gallons per minute. Using the metric system the amount is the more impressive, totaling 1 billion liters of water per year. The quantity, if thoroughly developed, would be about half the capacity of France’s Perrier Vittel or Italy’s San Pellegrino.

Currently the Trinity

operation takes only 26 gallons per minute during regular bottling

hours. Water is stored in large tanks before it is bottled in various

sizes using an advanced European bottling system that seems uniquely out

of place in the natural setting of the spring. The integration of

technology was a sensitive process for the architects who designed the

springhouse and the bottling barn, which houses conveyor belts, piles of

PET recyclable plastic bottles and caps, miles of labeling ribbon and

the filling spigot.

Because faults in the granite that allow the water to reach the surface

are lined with crystals, there is a temptation to make broad claims

about the powers of the water as many labels on grocery shelves do with

fancy nature names and promises of health benefits. Many claims may be

as transparent as the plastic bottle containing the fluid. Some

alternative healers would say the power of the crystals cannot be

denied, but Trinity avoids the pitfalls of health claims.

Roy Johnson says part of his job is to steer the company clear of promises it can’t keep about the health benefits of the water, which are difficult to prove. He is a scientist, after all.

“It won’t keep your hair from turning gray,” he admits.

When the bottling plant is not in production, the spring is allowed to flow to its natural water course that pours through a small Tilapia fish pond previous owners developed as part of their own commercial venture.

The fish are the size of medium gold fish. They could be bigger, but Roy doesn’t feed them.

“They are my canaries,” he jokes, just in case something serious happens to the water quality.

By law, water cannot be called “organic” but Trinity is a Quality Assurance International (QAI) certified source, the first independently certified source in the country.

Trinity’s slogan is “Source Matters.” Straight from the ground, the Trinity water contains only the elements and compounds silica, sulfate, chloride, fluoride, sodium, calcium and potassium. That’s it. Municipal water systems and the big bottled water products like Coca-Cola’s Dasani and Pepsi-Cola’s Aquafina have to contend with assuring water quality through chemical treatment—purification is required.

Directly

adjacent to the source, water is piped through the Trinity bottling

plant, where it is cooled, capped and boxed for shipping. photo

by David N. Seelig

Directly

adjacent to the source, water is piped through the Trinity bottling

plant, where it is cooled, capped and boxed for shipping. photo

by David N. Seelig

“It is clean water,” says Johnson. But, not all bottled water is as highly regulated or frequently tested for contaminants like E. coli or fecal coliform as municipal water, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Tap water from surface sources must be tested for viruses, bacteria and other organisms, but bottled water can slip through the cracks.

Because of the high mineral content of Trinity water, it is classified as a mineral dietary supplement. If it were just bottled water, by law, it would be disinfected. Avoiding the neutralizing impact of disinfecting, Trinity maintains components that help to make it beneficial for health.

Analysis by U.S. food authorities and the world famous Institute Fresenius laboratory in Frankfurt, Germany, show the springs to be “one of the highest quality water sources in the world.” In fact, the institute gave the source the first Naturliches Heilwasser designation in North America, which is water with healing properties.

If the company can hold onto the certifications for 500 years, it may qualify to be as pure as German beer.

In the meantime, Trinity is quashing international competition in the bottled water industry anyway, if not in quantity at least in quality. According to Spence Information Services that releases scanner data every month, in the four-week period ending Aug. 2, 2003, in the North American natural foods market Trinity outsold two other mineral spring waters, Penta and Fiji, and sold almost twice as much as Evian.

Although all water is heavy by weight, Trinity water is less “heavy” than most water at the surface of the earth because it contains no tritium, an isotope of hydrogen that is heavier than normal hydrogen. The lack of the isotope in Trinity water is an indication of its lack of contamination by the modern world. The batholith protects the ancient water.

When the three

springs and three founders came together at the base of the Trinity

Mountains, Johnson, Bell and Acker set aside complex ideas of

hydroponics and fish and focused on the basics.

The source, coming directly to the surface after a 16,000-year cycle

begins as rain or snow precipitation. Over eons the water soaked into

the granite batholith, became purified as it passed through the rock.

Pressure of the water saturating the batholith and heat from the earth’s

core forced the water through faults back to the surface.

“The water is more than boiling at depth,” Johnson said. “It is a system like hot springs in Yellowstone. It is a gentler geyser with a significantly different mineral consistency than Old Faithful.”

Trinity water has a pH of 9.6, which is quite alkaline. Some health care providers argue that the alkalinity helps counteract acidic lifestyles. It is also rare to have as low a sulfide content as Trinity does, Johnson says, so it doesn’t smell like a hot spring when you open the bottle.

To mitigate concerns about getting too many minerals in a day, Trinity makes a second product called geothermal water, which is part distilled water and part plain original Trinity source water. The water is considered an all day “drinker.”

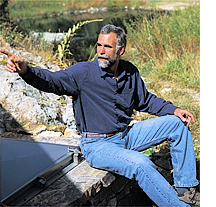

Trinity water chief scientist Roy Johnson tells how it all began. Today, the company still only takes of the resource what the earth will provide. Under Johnson’s direction Trinity keeps a close eye on the purity of its source. photo by David N. Seelig

The stewards of the source, Trinity water master Guenter deVincent, Roy Johnson and bottling plant manager Rick Franklin all helped to hand-build the capture basin and stone springhouse. The bottling plant, about two steps from the springhouse, is a unique mix of New Mexican stucco and a Wisconsin dairy farm. There is an amazing transition from the crystal-lined opening where the water emerges from deep in the earth through a stainless steel pipe to the industrial interior of the bottling plant. The water is cooled a few degrees to avoid compromising the plastic bottles, and the captured BTUs are used to heat the plant.

How much more of the market Trinity will take is unclear, but plans are for growth, said Johnson.

“We need to make money for our shareholders,” he said.

The company faces few obvious hurdles, although some people have questioned the company name. Some people read the label for its religious overtones, Egan says. It suggests a Christian spiritual connection. The water is also certified Kosher.

“Some Christians ask, ‘don’t you have a problem with the kosher designation and having the name Trinity?’”

“There are many paths to God,” she responds. “Drink this.”