Photo by David N. Seelig

A Fork of History

Languishing idly in a tributary of the Salmon River, the massive Yankee Fork gold dredge stands as a testament to the engineering feats of our forefathers. Pat Murphy explores this relic of Idaho's frontier mining history. Photos by David N. Seelig.

Ghostly remnants of another Idaho mining boom-and-bust linger along the nine miles of dirt road just north of the Sunbeam Dam and Yankee Fork turnoff on state Highway 75. Wooden shards, remnants of homes that once occupied the exuberantly named settlement of Bonanza, lay between the trees. Cabins, better-preserved icons of what passed for civilization in the 19th century wilderness, stand farther along the road in Custer. Between these relics of the Old West looms a brooding artifact, a younger cousin to those mining yesteryears that seems, at first glance, to be just a mirage in the backwoods of lush forests and richly stocked fishing streams.

The word behemoth is insufficient to describe the giant Yankee Fork gold dredge. It is a grayish monster languishing in its final resting place, a mechanical dinosaur idling in a perpetual pond, now serving only as a fascinating curiosity for tourists. Turn the clock back 60 years and the dredge resembled a well-lighted, four-story hotel; and it had a purpose. It spent its days swinging a giant arm to gouge and sift earth by the tons per minute in search of gold.

Mining history swells with tales of gargantuan dredges such as the Yankee Fork’s, carted piecemeal through forests and over mountains into remote areas, then floated in small pools of water to endlessly gouge alluvial deposits in search of precious minerals. Although precise numbers are debated, Idaho state historian Larry Jones says perhaps as many as 20 gold dredges operated throughout Idaho.

The

switch from digging tunnels deep into mountain faces to scouring drainages

for precious flakes of gold occurred mid-century. After the mines and mill

closed in 1911, Custer and Bonanza became ghost towns. For 20 years only a

few miners and the occasional sheepherder passed through. As dredging

replaced older mining practices and testing showed about $11 million in gold

still in the Yankee Fork valley, interest and investment from Eastern

financiers led to the construction of the Yankee Fork dredge in 1940.

The

switch from digging tunnels deep into mountain faces to scouring drainages

for precious flakes of gold occurred mid-century. After the mines and mill

closed in 1911, Custer and Bonanza became ghost towns. For 20 years only a

few miners and the occasional sheepherder passed through. As dredging

replaced older mining practices and testing showed about $11 million in gold

still in the Yankee Fork valley, interest and investment from Eastern

financiers led to the construction of the Yankee Fork dredge in 1940.

Idaho potato magnate J.R. Simplot, who purchased the dredge in 1950 for the bargain price of $75,000, searched for gold—how successfully isn’t precisely known—until he shut it down in 1952. He reportedly said of his few years operating the dredge, “The old girl was good to me.” Simplot eventually donated the dredge to the U.S. Forest Service. Neglected and vandalized, the dredge was rescued by volunteers of the Yankee Fork Gold Dredging Association, which now conducts tours, accepts donations and operates an onboard souvenir shop during the dredge’s season between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

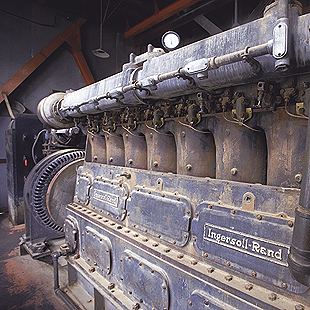

The Yankee Fork dredge, weighing 988 tons, was built at a cost of $428,304 by the Bucyrus-Erie Company. Two 450-horsepower Ingersol-Rand diesel engines provide power. Essentially a large barge, the dredge is 112 feet long and 54 feet wide, with a four-story superstructure that is 64 feet high. The dredge houses enormous machines that once gobbled and ingested raw earth through 71 gaping, 1-ton, mouth-like buckets on a continuously revolving belt, sifting rock through several washing processes, retaining small deposits of gold, then spewing unwanted residue out the dredge’s rear onto tailings piles.

Mechanically, the dredge is a Neanderthal alongside today’s microchip, laser and robotic industrial technology. But in its day, the gold dredge was a marvel of efficiency that even now inspires awe and admiration in Elmer Smith, 69, a onetime professional baker and now devoted volunteer and manager of the dredge’s six volunteer guides. Smith’s association with dredges dates back to the Alaskan frontier where he assembled one to dig for platinum.

Leading

the way upstairs and through the cavernous innards of the dredge while

describing the once deafening, “round-the-clock running machines,” Smith

points to apparatus with such dumbfounding names as bull gear, trommel,

stacker, cleanup jig and swing winch. At the high point of the dredge, in

the operating cabin, Smith simulates the role of winch man, who pulled and

pushed large, chest-high iron levers that engaged the digging machines,

whose clinking and clanking and roar was a relentless sound reverberating

through the drainage. The process of sifting precious little gold from tons

of raw earth can best be compared to a giant washing machine. Yet, enormous

as it was, the dredge required only three onboard crewmen and two on shore

in each of three, eight-hour shifts per day. Their pay was anywhere from 62

cents to $1.25 in 1940, scant higher in 1952.

Leading

the way upstairs and through the cavernous innards of the dredge while

describing the once deafening, “round-the-clock running machines,” Smith

points to apparatus with such dumbfounding names as bull gear, trommel,

stacker, cleanup jig and swing winch. At the high point of the dredge, in

the operating cabin, Smith simulates the role of winch man, who pulled and

pushed large, chest-high iron levers that engaged the digging machines,

whose clinking and clanking and roar was a relentless sound reverberating

through the drainage. The process of sifting precious little gold from tons

of raw earth can best be compared to a giant washing machine. Yet, enormous

as it was, the dredge required only three onboard crewmen and two on shore

in each of three, eight-hour shifts per day. Their pay was anywhere from 62

cents to $1.25 in 1940, scant higher in 1952.

The marvel of the Yankee Fork dredge, as with all of the species, was the ability to float on 25 large pontoons in its own self-dug 8-foot-deep pond, and move the pond along as the giant bucket line arm swung slowly from side to side and up and down like a huge elephant trunk, gulping up earth to be washed and sifted. It could only make about seven complete swings of 60 to 80 feet each in 24 hours. A 17-ton “spud”—a giant, retractable anchoring pole drilled into the ground—allowed the dredge to swing side to side without moving fore or aft. During its career, the ponderous Yankee Fork dredge chewed its way through a mere 5-mile-long stretch known to contain minerals close to the surface.

The official record shows the Yankee Fork dredge operated for 61 months of its eight-year working life, from 1940 to 1952 (it was shut down during World War II between 1942 and 1946). In that time, it reportedly cost an average of a penny more per cubic yard to dig (17 cents) than per cubic yard earned (16 cents), although earnings reached 33 cents per cubic yard in 1952 toward the last days of operation. Total minerals income was $1,037,323 (gold, $1,023,025 and silver, $14,298) from 6,330,000 cubic yards of earth dug at a cost of $1,076,100.

If massive mining mastodons such as the Yankee Fork dredge are now merely curious relics, their basic technology lives on. Small, portable, backpack dredges with suction pipes, weighing as little as 40 pounds, are in use by prospectors searching for gold around the world. But few creations remain as impressively awesome as the giant inland dredges that momentarily held the stage in the evolution of industrial machines.

Photo by David N. Seelig

Visiting the dredge

The

Yankee Fork dredge is open daily for tours from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. from the

last weekend in May through Labor Day. Only 83 miles from the Ketchum/Sun

Valley area, the dredge can be reached in two hours. Follow state Highway 75

for 13 miles east of Stanley, then turn north at the Sunbeam Dam onto the

Yankee Fork Road and follow the dirt road for nine miles. The $3 fee for a

guided tour is used for the preservation of the dredge and the heritage of

the Yankee Fork.

The

Yankee Fork dredge is open daily for tours from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. from the

last weekend in May through Labor Day. Only 83 miles from the Ketchum/Sun

Valley area, the dredge can be reached in two hours. Follow state Highway 75

for 13 miles east of Stanley, then turn north at the Sunbeam Dam onto the

Yankee Fork Road and follow the dirt road for nine miles. The $3 fee for a

guided tour is used for the preservation of the dredge and the heritage of

the Yankee Fork.