Photo illustration by David Keiski

A valley ablaze

In just seven days, the Valley Road Fire consumed 40,838 acres of White Cloud mountain country. Its voracious flames threatened lives, destroyed miles of popular trails and killed thousands of fish. Shea Andersen gets up close and personal with the largest fire in the history of the Sawtooth National Forest.

The dawn of Saturday, September 3, 2005 was warm, windy and dusty in the Sawtooth Valley. A caretaker for a local ranch property decided today was a good day to burn trash. As winds gusted across the dry, sagebrush foothills, embers of burning garbage escaped the old, rusty barrel, sparking tiny fires among the sage.

For 40,838 acres of White Cloud mountain country, that was it. The largest fire in the history of the Sawtooth forest began, setting records for the area, tangling lives and endangering others.

Mine was among them.

Conditions for a big forest fire, the sort that chews through the countryside’s sagebrush and timber, take time to develop. They can also depend largely upon chance, stupidity or bad luck. The correct or, more precisely, unfortunate set of circumstances can turn an area that once elicited only concern into the scene of a modern outdoor drama. On that sunny September day, 40 miles north of Sun Valley, several necessary elements were already in place.

Mother Nature had provided the fuel: large swaths of distinctive reddish-brown, the palette of insect infestation in the forest. Over the years, pine and fir trees in the Sawtooth and White Cloud mountain ranges had fallen victim to the appetite of the Rocky Mountain pine beetle. The infection attacked the dominant tree in the area, the lodgepole pine, leaving behind more than a million dead and dying trees loaded with dried needles.

Climatic

conditions provided just the right atmospherics: low humidity, breezes up to

25 miles per hour and temperatures in the high 70s. It was the sort of

weather that makes it easy to dry clothes on an outdoor line—with strong

enough clothespins. The Haines Index, a set of indices that combines weather

instability with dry air to help determine the potential for large fire

growth, was high.

Climatic

conditions provided just the right atmospherics: low humidity, breezes up to

25 miles per hour and temperatures in the high 70s. It was the sort of

weather that makes it easy to dry clothes on an outdoor line—with strong

enough clothespins. The Haines Index, a set of indices that combines weather

instability with dry air to help determine the potential for large fire

growth, was high.

But these conditions merely set the stage for the human actors that pepper Sawtooth country.

On the Friday before that Labor Day weekend, Ed Cannady, backcountry recreation manager for the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, had his mountain bike in his car and was headed out to ride Fisher Creek Trail. Like many others, he saw the dead pines, combined with the unsettled, hot weather and worried. “I said, ‘Man, one cigarette out a car window and this is going up,’” Cannady recalled.

But days like these had come and gone. In the previous 20 years, 209 wildfires had started in the Sawtooth Valley area, between them burning just 350 acres. The forest simply does not have a history of large wildfires. Foresters call it a “long fire return interval forest”—only every 150 to 200 years is a significant fire to be expected. Each of those 209 flickering flames had the potential to be that significant fire, but from each, a vital element was missing. Be it a lack of wind, something blocking the fire’s path, or a speedy response by local firefighters, some skill and a whole lot of luck had repeatedly combined to prevent the forest from exploding.

As the 756,000 acres of the SNRA gradually filled with hikers, mountain bikers and tourists out to enjoy the unseasonably warm Labor Day weekend, six friends, three dogs and I parked our cars by the Fourth of July Creek Trailhead, at the end of the winding, rock-strewn road that stretches from Highway 75 up into the lodgepole pine forests. We hiked into the Chamberlain Lakes area, and Friday night saw us stretching out under the stars, marveling at the warm, dry weather. By Saturday, we had walked another several miles to Castle Peak basin, an imposing landmark with several scenic lakes at its base. As we set up our second night’s camp, we noticed a plume of smoke rising silently over the horizon.

The

plume was also visible from the nearby city of Stanley. Steve Anderson,

assistant fire management officer for the north zone of the Sawtooth

National Forest, was among the first on the scene of the fire. He arrived at

the ranch property just in time to watch flames march from sagebrush-covered

flats to the dry timber in the upper foothills.

The

plume was also visible from the nearby city of Stanley. Steve Anderson,

assistant fire management officer for the north zone of the Sawtooth

National Forest, was among the first on the scene of the fire. He arrived at

the ranch property just in time to watch flames march from sagebrush-covered

flats to the dry timber in the upper foothills.

“Obviously, it was ripe from a fuels standpoint,” Anderson said. “There was plenty of fuel for it to burn. What was unnatural was the ignition.” Pilots, firefighters and civilians who flew low over the fire’s blackened mark said it was undeniable: The black grew in a fan shape from a single point—the burn barrel on a ranch along Valley Road.

“Burn barrels,” Anderson said, “are not a part of the lodgepole ecosystem.”

According to Anderson, the equipment, helicopters and firefighting personnel he was able to amass were not enough to prevent the fire from erupting. A variety of events had combined to siphon his resources away from him. Traffic, created by the annual Wagon Days parade in Ketchum, held up engines responding from districts south of the SNRA. A false alarm in the East Fork drainage to the south detained them further. Anderson and his crews stuck with the Forest Service’s first priority in such situations: Protect human life and structures by any means necessary. “Mother Nature can overwhelm us,” he said.

When a fire climbs into the trees and beyond, its evolution is owed to factors other than those mustered up by government dollars. Human toil cannot stop it. Norman MacLean, author of Young Men and Fire, describes that moment a fire makes the crucial leap from ground-creeping blaze into another thing entirely: a crown fire.

“An old-timer knows that when a ground fire explodes into a crown fire with nothing he can see to cause it, he has not witnessed spontaneous combustion, but the outer appearance of a ‘fire triangle’ suddenly in proper proportions for an explosion—The new firefighter doesn’t know how his fire got way up there. He is frightened and should be.”

A

crown fire leaps from treetop to treetop, independent of the surface fire.

It is self-perpetuating; it creates its own weather and generates its own

wind. Firefighters can do little to stop it—managing its direction becomes

preferable to the dangerous, inordinately expensive and likely impossible

notion of trying to put it out.

A

crown fire leaps from treetop to treetop, independent of the surface fire.

It is self-perpetuating; it creates its own weather and generates its own

wind. Firefighters can do little to stop it—managing its direction becomes

preferable to the dangerous, inordinately expensive and likely impossible

notion of trying to put it out.

That first day, the fire gobbled up land at a pace of seven acres per minute, a pace it almost doubled on Sunday.

I was too ignorant, just yet, to be frightened. That would come on Sunday. I might have been had I the vantage point of Matt and Jody Bullard.

The Bullards, residents of Boise, were spending the weekend backpacking into Fourth of July Lake with their dogs Ketchum and Cassidy. Like my group and several others in the woods that weekend, they parked their car, a 1996 Volvo station wagon, at the Fourth of July Trailhead parking lot. On Sunday, the Bullards were climbing a high ridge above Fourth of July Lake.

The day before, they too had seen the plume of smoke coming from the foothills below the trailhead. They went to bed, woke up and saw no smoke—the fire had calmed briefly Sunday morning. By the time the fire woke up again, the Bullards had hiked to a high ridge. When they saw a helicopter landing near the lake they’d slept beside and Forest Service rangers jumping out, they decided it was time to return.

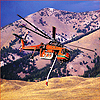

Cannady was in that helicopter. He’d climbed aboard after meeting with Matt Filbert, fuels planner for the north zone of the Sawtooth National Forest, to discuss how to extract dozens of hikers and their vehicles from what was about to become the center of a voracious fire.

“Suspense doesn’t do it justice,” Cannady said. “What I was experiencing was fear. We didn’t know who else was out there. The unknowns were terrifying. That was one of the wildest days of my career, because of those unknowns.” While Filbert connected with firefighters, Cannady and others developed the evacuation plan to locate and fly out hikers and, in the Bullards’ case, their dogs.

At

first, the Bullards were prepared to endure the 14-mile trek out to Warm

Springs Creek to get their dogs out safely. Five minutes after agreeing to

that with Cannady, a radio call came from Forest Service dispatch informing

them it was not safe to walk out—the fire was growing too rapidly. Already,

another walkable exit—a treacherous climb over a mountain pass—had been

ruled out because of increasing fire danger. After a discussion between

Cannady, the dispatcher and helicopter pilot Chris Templeton, Cannady

approached the Bullards. Matt recalled, “He looked me right in the eye and

said, ‘Are your dogs cool?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ Their chief concern was saving

lives and they did an outstanding job.”

At

first, the Bullards were prepared to endure the 14-mile trek out to Warm

Springs Creek to get their dogs out safely. Five minutes after agreeing to

that with Cannady, a radio call came from Forest Service dispatch informing

them it was not safe to walk out—the fire was growing too rapidly. Already,

another walkable exit—a treacherous climb over a mountain pass—had been

ruled out because of increasing fire danger. After a discussion between

Cannady, the dispatcher and helicopter pilot Chris Templeton, Cannady

approached the Bullards. Matt recalled, “He looked me right in the eye and

said, ‘Are your dogs cool?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ Their chief concern was saving

lives and they did an outstanding job.”

Before long the Bullards were on board the helicopter with Ketchum and Cassidy perched between their legs, definitely not a traditional flight crew. “The dogs weren’t even shaking,” Matt said. “They just froze and let us sort of manhandle them. They knew something was going on.”

In all, 22 people at Fourth of July Lake were evacuated that day. During the course of the fire, 55 homes downriver from Stanley and 30 in the Fisher Creek area were placed under evacuation notice.

Over a mountain pass from the flying Bullards, my group and I were stuffing gear back into our packs with a directive from backcountry ranger Jocelyn Brown to head out of the wilderness via a route to a trailhead farther from the fire, where Forest Service trucks would pick us up. We hiked ever faster, turning to watch the plume grow into a ground-level storm of gray smoke. It was headed our way.

After spending three college summers working on a forest firefighting crew in central Idaho, I figured I’d had my share of hair-raising experiences. Since those days, I’d happily stayed away from anything larger than a backyard bonfire. With a smoke column obscuring most of the view behind us, I realized I was closer to a serious fire than I’d been in years.

I

boiled it down to a choice for my friends who, I feared, weren’t hiking fast

enough to stay ahead of the flame front: Move faster toward the safety of

the trailhead or go to the creek below and hunker down in the water with

hopes it would be sufficient—no guarantees existed—to protect them from the

fire. They chose to hike faster than they ever had before. We hotfooted it

to safety, waiting breathlessly for the arrival of green Forest Service

trucks.

I

boiled it down to a choice for my friends who, I feared, weren’t hiking fast

enough to stay ahead of the flame front: Move faster toward the safety of

the trailhead or go to the creek below and hunker down in the water with

hopes it would be sufficient—no guarantees existed—to protect them from the

fire. They chose to hike faster than they ever had before. We hotfooted it

to safety, waiting breathlessly for the arrival of green Forest Service

trucks.

But as we boarded our chauffeured rides out of the wilderness, our cars remained in the middle of the fire zone. “Even though the vehicles were the lowest priority, logistically they were the greatest liability,” said Filbert. While Cannady quizzed hikers about hidden car keys, a cadre of rangers did everything short of shaking the cars to see if they could locate keys. “We were scratching it thin, time wise,” Filbert said.

In the end, they safely evacuated all seven remaining cars, chain sawing their way through the debris up the smoke-filled canyon. Even Bullard’s old Volvo, with its low clearance, made it out through the rubble. To this day, Bullard said, sensitive passengers in his car can pick up a whiff of wood smoke.

After my evacuation, I sat at the Sawtooth Valley work center just south of the fire, watching flames stretch to ludicrous lengths, nearly 100 feet, as they devoured stands of dry trees.

For the next several days high winds and low humidity kept the fire rolling, consuming up to 10,000 acres each day. Fire managers quickly saw that, as the now-named Valley Road Fire grew, it would take many more firefighters to stop it. Within two days, Forest Service officials assigned a Type 1 Incident Command Team, a sure indication of the fire’s catastrophic potential. Such teams travel the country responding to natural disasters, like last year’s Hurricane Katrina.

During the first week

more than 1,000 firefighters and support personnel crawled over the fire,

under the constant din of nine helicopters dropping water and retardant on

and ahead of the flames. At its peak the fire’s rapidly advancing front was

more than eight miles wide, marching toward the Salmon-Challis National

Forest. One fiery leap over the Salmon River and tens of thousands more

acres of fresh, beetle-killed pine lay in its path. The fire’s huge

mushroom-shaped plume reached up to 35,000 feet and was visible 150 miles

away in Twin Falls.

The Valley Road Fire was making a name for itself as a fire with an

attitude.

Sitting

in the now-bustling fire camp between Champion Creek Road and Highway 75,

Colleen Decker, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, had been

called in to put the Valley Road Fire into perspective and help firefighting

teams understand what the day’s weather might do to fire behavior.

Sitting

in the now-bustling fire camp between Champion Creek Road and Highway 75,

Colleen Decker, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, had been

called in to put the Valley Road Fire into perspective and help firefighting

teams understand what the day’s weather might do to fire behavior.

In firefighting jargon, crews sometimes refer to nonhuman firefighters that will ultimately prevail where men and women with tools cannot.

Sometimes it is the “CNA,” also known as “cold night air,” that knocks a fire down to a manageable size. For an unruly blaze such as Valley Road, firefighters and meteorologists like Decker were hoping for something more dramatic. They got it.

On September 10, seven

days after the fire began, a cold front settled in to the Salmon River

Basin. According to Decker’s data, almost three inches of snow fell on

firefighters sleeping at the fire camp by Highway 75. Up the hill at the

fire, she said, accumulations were more like four to eight inches of wet,

heavy snow. “That did the job,” said Decker. “It was a really good example

of a season-

ending event.”

At a Forest Service station elsewhere in the valley, Cannady went out and danced in the falling snow. In the valley, a hush fell over the blanketed fire camp, much in the way a snow-filled street suddenly seems quieter. Although isolated torching and some spread continued to keep firefighters on the scene for weeks longer, the Valley Road Fire had been sucker-punched. On September 28, the fire was officially declared contained; firefighters had effectively hemmed the fire in through natural firebreaks and by cutting more than 30 miles of hand-cut fire line. Some of the army of fire crews began to move out, off to the next conflagration, somewhere without snow.

The flames may have been gone, but putting a fire out is just the beginning. Another type of crew was quickly dispatched into the White Cloud Mountains, a BAER crew. The Burned Area Emergency Response crew’s mission is to assess the damage and develop a plan to help the land and streams recover.

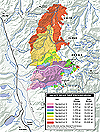

Forest

Service biologist Terry Hardy led a crew of 21 foresters on several trips

into the burned area, determining what impact the blaze had on the White

Clouds. Although the fire burned hot in places, it skipped others. Still

other places were moonscaped, firefighting slang for areas where flames

burned so hot the land no longer resembles Earth. About 34,000 acres of the

Valley Road Fire’s 40,838 acres, Hardy said, burned hot enough to get a

moderate-to-high severity rating.

Forest

Service biologist Terry Hardy led a crew of 21 foresters on several trips

into the burned area, determining what impact the blaze had on the White

Clouds. Although the fire burned hot in places, it skipped others. Still

other places were moonscaped, firefighting slang for areas where flames

burned so hot the land no longer resembles Earth. About 34,000 acres of the

Valley Road Fire’s 40,838 acres, Hardy said, burned hot enough to get a

moderate-to-high severity rating.

A chief concern was the impact on soil. When exposed to the high heat of a roaring forest fire where temperatures average 1,600 degrees Farenheit (aluminum melts at 1,200 F), soil can lose its ability to hold water, contributing to landslides and impeding vegetation growth.

In the hard-hit Warm Springs, Fourth of July and Champion creeks, fish were killed—either cooked alive or deluged with ash and dirt—in such numbers biologists would only refer to them as “extensive fish mortalities.”

Recreation specialists such as Cannady also bemoaned the loss of miles of popular trails.

A $1.7 million rehabilitation plan to protect the area began quickly, before snow fell in greater depths. Forest Service rehabilitation specialist T. J. Clifford said 1,892 acres of the blackened area received straw-mulch applications in hopes the straw would stimulate and protect new plant growth. Four helicopters from Utah and Idaho, alongside dozens of reforestation crews, worked the fire’s black scar, spreading nearly 1,500 tons of weed-free straw.

That, Clifford said, is just the beginning. “The monitoring we will be doing over the next three years is to basically determine the effectiveness of the rehabilitation work that we are doing.”

The Valley Road Fire will always raise more questions than answers. Among the most curious to locals is what might happen to the caretaker of the ranch on Valley Road. Forest Service officials have declined to name the individual, and the owners of the ranch did not respond to several telephone inquiries for this article. For now, officials said, no criminal charges will be filed. The statute of limitations is six years, according to Ed Waldapfel, the Sawtooth National Forest’s spokesman. During that time officials will likely gauge how much of a fine to levy against a seasonal caretaker who is probably unable to cover the nearly $7 million—and counting—in firefighting and rehabilitation costs.

Those who felt the Valley Road Fire up close and personal are not fooled about the inevitability of future wildfires in the area. The fire consumed just one small part of a massive, forested area. As new residents move into Idaho and push closer to bug-killed forests, the likelihood of more flames licking too close for comfort will always be present.

Tim Sexton, incident commander of the fire, summed it up: “The Sawtooth Valley is still a catastrophe waiting to happen, due to dense, unburned stands of beetle-killed lodgepole pine on the west side of Highway 75.”

Some, like Filbert, are hoping the Valley Road Fire might ultimately be helpful. “Overall, it was probably a typical fire,” he said. “Human-caused or not, that’s probably the way we should expect fires to burn in lodgepole pine and mixed conifer ecosystems.”

Only time will tell what Mother Nature has in store for the forest. One thing that has gradually become clear to foresters and researchers over the past 40 years is that fire is part of her plan. Many researchers now hold new beliefs about fire’s beneficial impacts. Fire rids a forest of diseased and dying timber, diversifying wildlife habitat and allowing for the growth of new forestlands.

It is a new neighbor, this sort of fire, but, as most foresters and researchers agree, it isn’t going anywhere. The challenge now is to see it as an inevitable neighbor and maybe even a beneficial one.

Photo by Susan Van Der Wal

Killer beetle

In the last 10 years, the Sawtooth National Recreation Area’s forests began

changing so much that visitors to the Stanley Ranger Station in the Sawtooth

Valley began to ask, with some frequency, what was going on. People, seeing

swaths of dead timber, wondered just how sick the forest was.

Foresters argue the current die-off of thousands of lodgepole pines in the area is not unnatural, nor is this the first time it has happened. Drought and opportunistic insects combine to change the forest makeup. “Up here, the mountain pine beetle is doing its thing,” said Matt Filbert, a fuels planner for the Forest Service.

Foresters estimate that between 1999 and 2002 the number of lodgepole pines killed by the Rocky Mountain pine beetle rose from 8,183 to 845,000 in the Sawtooth National Forest. The latest estimate, taken from an aerial survey in 2005, is more than a million trees on approximately 90,000 acres have been affected by the beetle.

The bug is a natural visitor to lodgepole pine forests of about 80 years or older. It is a lousy guest, filling up vital circulation channels in trees, which eventually die as the beetles proliferate. Foresters emphasize that there is no controlling a beetle outbreak. Instead, they hope a combination of human controls, natural fire and new growth will reduce beetle infestations over time.

Photo by Lynne Stone

Recreational use

after the fire

The following is a list of hiking and mountain bike trails affected by the

Valley Road Fire— some have just portions affected, others have been totally

destroyed:

• Pigtail Trail (Fisher Creek Trail)

• Fisher Creek Loop

• Williams Creek Trail to Warm Springs Meadow

• Warm Springs Creek to four miles from Robinson Bar

• Martin Creek from the meadows up for three

to four miles

• Garland Creek Trail, the first three miles

• Champion Creek Trail

• South Fork Champion Creek Trail for about one mile

• Fourth of July Creek, Washington Lake Trail

The Forest Service strongly encourages hikers and bikers to check with the

Sawtooth National Recreation Area offices in Stanley, Redfish Lake Visitor

Center and the SNRA headquarters north of Ketchum for current trail

conditions prior to making their trip. When hikers, bikers and horse riders

come across trees that have fallen on burnt trails, they should go over the

obstacle, not around it. Going around creates more damage to ground cover,

resulting in erosion.