| click here for the |

| front page |

| features |

| fire lookouts |

| flytying |

| beavers |

| craters of the moon |

| arts |

| peter woytuk |

| printmaking |

| handmade guitars |

| living |

| high desert gardens |

| pavers |

| summer fitness |

| recreation |

| skateboarding |

| danny thompson mem |

| galena |

| dining |

| salads |

| margaritas |

| calendar |

| summer 2003 |

| to-do |

| sun valley essentials |

| listings |

| galleries |

| dining |

| lodging |

| fitness |

| golf |

| equipment rentals |

| outfitters + guides |

| maps |

| ketchum street map |

| sun valley street map |

| local art galleries |

| Galena summer trails |

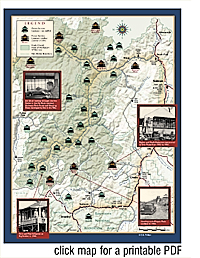

| fire lookouts: Idaho |

| fire lookouts: locator |

| the guide |

| last winter |

| advertising |

| about us |

| copyright |

| Copyright

© 2003 Express Publishing Inc. All Rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form or medium without express written permission of Express Publishing Inc. is strictly prohibited. |

| Produced

& Maintained by Express Publishing, Box 1013, Ketchum, ID 83340-1013 208.726.0719 Voice 208.726.2329 Fax info@svguide.com |

| The

Sun Valley Guide is distributed free twice yearly to

residents and guests throughout the Sun Valley, Idaho resort area

communities.

Subscribers to the Idaho Mountain Express will receive the Sun Valley Guide inserted into the paid edition of the newspaper. |

Room

with a View

Keeping an eye on 4.3

million acres

by Adam Tanous

This year I haven’t even been struck by lightning,” says Bernie Greenwald.

I’m not sure if he’s disappointed or not.

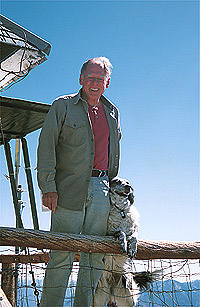

Greenwald, a well-spoken man of 63 years, spends his summers at the Pinyon Peak Lookout in the Salmon-Challis National Forest, a 4.3 million-acre expanse in east-central Idaho. His job, from this stunning perch above the Idaho wilderness, is to spot forest fires in their infancy.

He talks of his 28 years of spotting and fighting fires with the demeanor of a man who has been, on more than a few occasions, face to face with fire, lightning or both. He is humble and, perhaps most importantly, calm. He is also, as one might expect of someone who spends great stretches of time alone, an amiable man.

“When the lightning is even as far as 10 miles out, the hair on your arms and neck stands on end,” he says. “You can hear things buzzing. All of the antennas start to hum.” He gestures to the roof of the 14-foot by 14-foot building we are in.

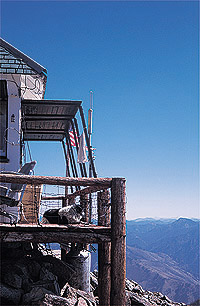

The lookout is a

box of wood and glass, this particular one built in 1930. Many of the

glass panes are the original ones, and they reveal their age. They have

a wavy quality, which reflects the fact that glass is a liquid and will

succumb to gravity over time.

The lookout is a

box of wood and glass, this particular one built in 1930. Many of the

glass panes are the original ones, and they reveal their age. They have

a wavy quality, which reflects the fact that glass is a liquid and will

succumb to gravity over time.

The building is on stilts set at the highest point of Pinyon Peak, a mountain 120 miles and a four-hour drive from the Sun Valley area. It seems farther. We are above the tree line at 9,942 feet, and so, while there is a sea of trees below, we are in landscape of granite boulders. The wind is blowing, as it always does up here. Nothing but the rich blue sky is above us for as far as I can see, 75 miles in every direction. We might as well be at the top of the world.

“When it’s 5 to 7 miles out, we don’t go outside.” Greenwald explains that there can be “spur strikes that peg out”—lightning that travels horizontally and, not incidentally, is invisible. “At 3 miles, we go out of service,” meaning he stays off the radio, his only connection to the greater world below. It can take up to an hour for the storm to pass.

“During that

time, I’m careful not to walk between the stove and the fire locator.”

Greenwald is referring to the Osborne Fire Finder, a device invented in

1920 for pinpointing smoke sightings in the vast forest that spreads out

around the lookout.

If Greenwald spots smoke in his territory, he goes to the Osborne to

determine the exact location of the fire, in terms of its legal

description—township, range and section. The device is basically the

center of a giant circle with a 20-mile radius. So using an Osborne Fire

Finder, a proficient lookout can pinpoint fires in an area of

approximately 1,256 square miles, assuming it’s flat terrain, which, of

course, it isn’t. The actual area is much greater.

The fire finder is

the central item in this small room that contains a bed, desk,

solar-powered radio, propane-powered fridge, wood-burning stove, shelves

for dry food supplies and books. Water, for drinking and washing, comes

in the form of “cubies”: boxes containing five gallons of water. The

water is brought in by a truck at the start of the year and is

intermittently re-supplied. Greenwald’s allotment is about two and

one-half gallons a day. Everything he needs for the summer is in this

room, including Maggie, his 12-year-old dog, an Australian shepherd and

border collie cross.

The fire finder is

the central item in this small room that contains a bed, desk,

solar-powered radio, propane-powered fridge, wood-burning stove, shelves

for dry food supplies and books. Water, for drinking and washing, comes

in the form of “cubies”: boxes containing five gallons of water. The

water is brought in by a truck at the start of the year and is

intermittently re-supplied. Greenwald’s allotment is about two and

one-half gallons a day. Everything he needs for the summer is in this

room, including Maggie, his 12-year-old dog, an Australian shepherd and

border collie cross.

While everything in the lookout is electrically grounded, it is by no means a foolproof system should lightning hit the building.

There is a phenomenon known as corona or point discharge. Fire lookouts refer to it as St. Elmo’s Fire. It occurs when the electric field strength potential between two points, say the fire locator and the stove, becomes greater than the resistance of the air in between. An electric current will, in a sense, jump through the air from the locator to the stove. The air, which is being ionized, will actually take on a bluish-white glow.

This is why, during a storm, Greenwald stays put on his wooden stool that has glass insulators on the legs. He seems to take it in stride that crossing his one and only room at the wrong time could cost him dearly.

“When it’s really on you, it’s not something I enjoy, to be honest,” he says.

Greenwald’s workday

is framed by three check-in times: 9 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. This is when

he gets on the radio to his fellow lookouts and the central dispatcher

in Salmon. It is a routine, I suspect, established to allow for

companionship as much as for safety. The rest of the day he scans the

forest around him looking for smoke—a task not as simple as it sounds

when you consider the vastness of the terrain he’s responsible for.

Also, sunlight spreading over wide swaths of land has a way of creating

illusions.

Greenwald’s workday

is framed by three check-in times: 9 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. This is when

he gets on the radio to his fellow lookouts and the central dispatcher

in Salmon. It is a routine, I suspect, established to allow for

companionship as much as for safety. The rest of the day he scans the

forest around him looking for smoke—a task not as simple as it sounds

when you consider the vastness of the terrain he’s responsible for.

Also, sunlight spreading over wide swaths of land has a way of creating

illusions.

“It’s not hard to see smoke if you’re patient,” Greenwald says. “It gets a little trickier if there are water dogs out there.”

Water dogs, he explains, are columns of water vapor that can look remarkably like smoke. The difference, he says, is that water dogs tend to be a little grayer in color; smoke is bluer.

“But when the spot is 10 to 15 miles out or farther, it’s difficult to tell them apart. First-year lookouts tend to call in a lot of water dogs. But, the way I look at it, every call is a good call, because it means the guy is out there looking.”

Even a person

calibrated to the clear Idaho skies will have a tough time figuring

distances from a lookout. It is much bigger country than the average eye

can size up. Greenwald asks how far I think a few ridgelines and peaks

are. I’m not even close. They are all much farther, by miles, than they

appear. It also underscores the value of experience. Greenwald has been

here six seasons and knows every peak, drainage and other geographic

landmark in his purview.

Even a person

calibrated to the clear Idaho skies will have a tough time figuring

distances from a lookout. It is much bigger country than the average eye

can size up. Greenwald asks how far I think a few ridgelines and peaks

are. I’m not even close. They are all much farther, by miles, than they

appear. It also underscores the value of experience. Greenwald has been

here six seasons and knows every peak, drainage and other geographic

landmark in his purview.

If Greenwald does spot smoke, he then fills out an “incident” sheet. For this one page report, he will have to determine the distance, longitude and latitude, the aspect of the slope, the fuel loading on the slope—whether it is timber, brush or rock—the air temperature, wind speed and humidity. Once a smoke report is called in, the Forest Service dispatcher in Salmon arranges for a helicopter to fly over the terrain to get a closer look.

“It gets pretty expensive right away, maybe $1,000 an hour just for the helicopter,” Greenwald says as a way of pointing out how seriously he takes his job. The implication is quite obvious: At that kind of burn rate, no one wants to be known for calling in a lot of false alarms.

The job is complicated by the fact that a fire can erupt even seven or eight days after a lightning strike. These are called “creepers.” Lightning might hit a fallen tree and, because there is not a lot of fuel there or it is moist, the fire just sneaks around the ground for a few days. If the weather changes, causing the air and fuel to dry up, the fire takes off. This is how a forest fire can seemingly come out of nowhere. It is also why Greenwald is vigilant for many days after a storm.

Once an incident is confirmed as a fire, anywhere from two to eight smokejumpers, loaded down with shovels, chainsaws and the ever-useful Pulaski, may be sent in to put down the fire for two or three days. Beyond that, the Forest Service employs aircraft to drop fire retardant or enormous buckets of water to fight the fire. Getting on the fires early—which hinges on having competent people in the lookouts—is critical.

Fire lookouts and the

people who staff them are in one sense an anachronism. In the early

1900s, there were extensive wildfires, culminating in the fire season of

1910 when 3 million acres burned in Idaho and Montana. The first

lookouts, little more than tree forts, were built subsequently. Under

Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps built most of the

lookouts from 1933 to 1942. During World War II the lookouts had another

role: They were used to scan the horizon for incoming Japanese aircraft,

even as far inland as Idaho.

Esther Morgan, an archaeologist in the Challis office for the U.S.

Forest Service, says there was a concerted effort by government agencies

to suppress forest fires in the Challis National Forest (now the

Salmon-Challis National Forest) after the big fires of 1919. Lookouts

were a big part of that effort. In the ’40s the use of fire lookouts

reached a peak. There were approximately 8,000 lookouts across the

nation’s forests. In Idaho alone, the number of lookouts once numbered

989. Now there are fewer than 200, although only about 60 are still

staffed. In the Salmon-Challis National Forest, there are 35 lookouts

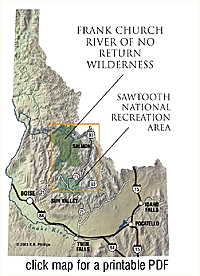

but only five are slated to be staffed in the summer of 2003 (see the

map on page 19). They are Pinyon, Ruffneck, Long Tom, Stormy and Twin

Peaks Lookouts.

Over the past 30

years, many lookout towers have been retired, destroyed or turned into

recreational facilities, cabins the public can rent out for an overnight

stay. Greenwald says three factors are chipping away at the need for

lookout towers and the people who staff them. One is the increasing use

of reconnaissance flights coupled with satellite detection of lightning.

Second is the advent of radio repeaters—electrical devices that boost

radio signals. Strong repeaters make it possible for lookouts to be

farther apart. Third, there is the issue of logistics.

Over the past 30

years, many lookout towers have been retired, destroyed or turned into

recreational facilities, cabins the public can rent out for an overnight

stay. Greenwald says three factors are chipping away at the need for

lookout towers and the people who staff them. One is the increasing use

of reconnaissance flights coupled with satellite detection of lightning.

Second is the advent of radio repeaters—electrical devices that boost

radio signals. Strong repeaters make it possible for lookouts to be

farther apart. Third, there is the issue of logistics.

Many of the lookouts are in wilderness areas like the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness—terrain in which motorized equipment of any kind is prohibited. The Wilderness Act of 1964 barred helicopters and planes from landing, as well as the use of cars and generators. So stocking a lookout with water, food, propane and other essentials became very difficult. They can be brought in on horseback, but that is not always so easy. Greenwald recalls packing in to the Big Creek Lookout in the “Frank” from the Chamberlain Basin—a two- to three-day adventure, which included fording fast-moving creeks that were as high as the stirrups of his saddle.

Greenwald loves his job, as do his colleagues in other lookouts. They tend to return year after year, provided the Forest Service continues to provide funding for their particular lookouts. Clearly the fire lookout system is caught up in the larger political debate about fire suppression and federal budgets. Still, Greenwald and his colleagues tend not to be consumed by the politics. They seem genuinely more concerned with the task at hand: keeping an eye on this remarkable beauty before them.

It is early September

when I visit Greenwald. There have been 60 confirmed incidents so far, a

“slow season,” he says. The peak fire month, August, has passed, when

there tends to be a lot of lightning and the fuel—trees, snags and brush

on the ground—is very dry. There have been no big fires in this forest.

The September days are shorter; there is less heat, more moisture.

Hunters are in the forest scouting the elk herds. Soon Greenwald will

head to Vancouver Island for some salmon fishing, then to Arizona for

the rest of the winter.

A “weather event”

ends the fire season. This is a wet blanket of snow that lasts.

Greenwald cleans out the cabin, changes the propane for next season,

shutters the windows and packs his bedroll. Then he and Maggie leave

their home atop this rocky peak and descend into the forest they have

been watching over all summer. Everything is standing tall.

A “weather event”

ends the fire season. This is a wet blanket of snow that lasts.

Greenwald cleans out the cabin, changes the propane for next season,

shutters the windows and packs his bedroll. Then he and Maggie leave

their home atop this rocky peak and descend into the forest they have

been watching over all summer. Everything is standing tall.