| click here for the |

| front page |

| features |

| fire lookouts |

| flytying |

| beavers |

| craters of the moon |

| arts |

| peter woytuk |

| printmaking |

| handmade guitars |

| living |

| high desert gardens |

| pavers |

| summer fitness |

| recreation |

| skateboarding |

| danny thompson mem |

| galena |

| dining |

| salads |

| margaritas |

| calendar |

| summer 2003 |

| to-do |

| sun valley essentials |

| listings |

| galleries |

| dining |

| lodging |

| fitness |

| golf |

| equipment rentals |

| outfitters + guides |

| maps |

| ketchum street map |

| sun valley street map |

| local art galleries |

| Galena summer trails |

| fire lookouts: Idaho |

| fire lookouts: locator |

| the guide |

| last winter |

| advertising |

| about us |

| copyright |

| Copyright

© 2003 Express Publishing Inc. All Rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form or medium without express written permission of Express Publishing Inc. is strictly prohibited. |

| Produced

& Maintained by Express Publishing, Box 1013, Ketchum, ID 83340-1013 208.726.0719 Voice 208.726.2329 Fax info@svguide.com |

| The

Sun Valley Guide is distributed free twice yearly to

residents and guests throughout the Sun Valley, Idaho resort area

communities.

Subscribers to the Idaho Mountain Express will receive the Sun Valley Guide inserted into the paid edition of the newspaper. |

Beavers

Idaho's Wetland Engineers

by Gregory

Foley

As the evening sun glistens on the pond, the beaver surfaces next to the dome-shaped lodge and begins to glide through the water. She paddles toward the dam, and then away toward the shaded shoreline, before lumbering into a shadowy grove of bright green aspens.

She gnaws on one of the smaller trees, first through the thin shell of bark, and then aggressively into the woody flesh. The leaves of the tree shimmer in the orange light, shaking with each thrust of the rodent’s oversized incisors.

The tree starts to lean toward the bank, falling slowly, when a resonant smack echoes off the valley wall. The beaver’s mate, a robust 60-pound male, rears his head from the shallows of the pond, and for a second time aggressively slaps his broad, fleshy tail on the surface to warn the female of an approaching coyote.

“Whack!”

The matriarch scurries to the water’s edge, the male dives, and the seemingly endless work of the beaver is left for another day.

Of the scores of wild creatures documented by early explorers of the American frontier, perhaps none has left its signature on the vast Western landscape more than the beaver.

Beavers once held dominion over most small waterways in the West, roaming the stream banks and wetlands by the millions. With each adult capable of cutting up to 300 trees per year, they dammed streams with cuttings to create networks of ponds and tributaries where they engineered small colonies of lodges. They felled aspens, cottonwoods and alders for food. On larger waterways, some dug dens and tunnels in riverbanks.

Streams,

brooks and rivulets across the West were slowed in their rush to lower

points in the landscape. Wetlands abounded, even in the high-desert

areas of Idaho and other Rocky Mountain regions. Fed by the richness of

the oases, plant life, fish, birds and a multitude of native animals

flourished in and around the colonies.

Streams,

brooks and rivulets across the West were slowed in their rush to lower

points in the landscape. Wetlands abounded, even in the high-desert

areas of Idaho and other Rocky Mountain regions. Fed by the richness of

the oases, plant life, fish, birds and a multitude of native animals

flourished in and around the colonies.

It is estimated that in the 1600s, between 60 million and 100 million beavers lived in North America, ranging across the continent. On their journey through the Northwest in the early 1800s, explorers Lewis and Clark regularly hunted beavers for food, taking special note of the animal’s industrious nature and unique ability to redirect streams.

A dozen or so years later, demand in Europe for the beaver’s thick fur coats—used to make fashionable top hats—fueled an unprecedented exploration of Idaho and other Rocky Mountain regions. Hardy men trapped beaver by the tens of thousands each year, with the trade reaching its peak in 1875, when the Hudson’s Bay Company sold more than 270,000 skins. By 1900, the aquatic herbivores were nearly extinct in the United States.

Hunted out of vast sections of its original range, the beaver in the 1900s stubbornly held on in some remote mountain areas, including Idaho’s Wood River Valley. However, beavers were heavily hunted in south-central Idaho in the 1800s, said Lew Pence, of Gooding, former chairman and coordinator for the Beaver Committee of the Wood River, a coalition of government agencies, environmental groups and private landowners that cooperate on projects to manage beaver populations and riparian habitat.

“Hudson’s Bay Company tried to eliminate beaver out of this area so trappers from the south would come up and think there were no beaver in the region,” Pence said. “They wanted to preserve their interests in the north of Idaho. They trapped thousands of beaver in Blaine County and Camas County.”

One group of trappers camped on the lower Big Wood River in 1819 reportedly became very ill from eating beaver meat, and subsequently used the French word for their sickly condition to name the waterway the “Malad” River, a name which still describes the lower section.

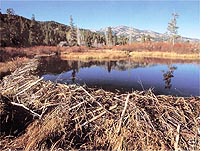

In recent years, with less demand for their pelts and more stringent management of trapping, the beaver has experienced a comeback in south-central Idaho. Signs of beaver activity can be seen in many parts of Blaine County and surrounding areas: felled aspens, cottonwoods and willows, latticed wooden dams that block slow-moving streams, and rounded lodges that stick up out of mountain ponds like small volcanic islands.

David

Skinner, wildlife biologist for the Sawtooth National Forest and current

chairman of the Beaver Committee of the Wood River, said the beaver

population of the Blaine County region is healthy, albeit much smaller

than it once was.

David

Skinner, wildlife biologist for the Sawtooth National Forest and current

chairman of the Beaver Committee of the Wood River, said the beaver

population of the Blaine County region is healthy, albeit much smaller

than it once was.

“We have a substantial beaver population that is probably expanding,” he said. “But it’s a small percentage of what was once here. Before trapping, I’m sure the whole Wood River Valley area was full of beavers.”

Skinner said thriving beaver colonies can be seen east of Trail Creek Pass, near Ketchum at the confluence of Lake Creek and the Big Wood River, in the Silver Creek Preserve near Picabo, in the sloughs of the Broadford area east of Bellevue, and along numerous streams east and west of the Wood River Valley, including the East Fork of the Big Wood. Beavers do not inhabit areas along the Big Wood River in large numbers, primarily because the river is too large for the animals to dam, he said.

The American beaver, Castor canadensis, is the largest rodent that lives in North America. An adult often weighs more than 50 pounds and reaches up to 4 feet long from the snout to the tip of its flat, scaly tail.

Beaver range throughout the continent, except in the Florida peninsula, the deserts of the Southwest and the Arctic tundra. In Idaho, they are well established in the northern and central parts of the state, where year-round water supplies provide ample food and aquatic habitat.

Strict vegetarians, beavers feed on a variety of tree and plant materials. They are famous for cutting and feeding on the bark of willows, aspens, cottonwoods and other deciduous trees, but also feast on aquatic plants and grasses. Despite their favor of mountain regions abundant with pine and fir, beavers do not eat the bark of coniferous trees. In winter months, they feed on piles of tree and shrub branches they store in underwater caches near their dens. They do not hibernate.

Beavers are perfectly equipped foresters and foragers. They can stay submerged underwater for up to 15 minutes, using their rudder-like tails and webbed hind feet for propulsion. The animals’ thick coats of fur—which allow them to endure extreme cold—are made waterproof through the application of specialized oil, called castor, that is excreted through two glands between their hind legs. Their mighty incisors can exert a chewing force twice that of an adult human. The teeth never stop growing and must be used regularly to keep them worn down to a manageable size.

American beavers live in colonies that are typically composed of five or six animals, although some family groups can grow to include as many as a dozen animals. They are predominantly monogamous creatures, especially the males of the species. Breeding pairs mate during the winter, and pregnant females typically give birth to two to four kits in late spring. The young stay with their parents until they are two years old, when they leave the colony to colonize new territories.

Beavers are typically relentless in their pursuits to construct and maintain their colonies; the mere sound of flowing water triggers in them an inexorable instinct to mend their dams. They can cut down a mature willow in minutes and build a dam in a few days.

Beavers build dams out of whatever materials they can collect near their chosen stream area, generally tree branches and brush packed with mud. Dams—which are engineered specifically to the size and type of the waterway—are employed primarily to establish a still, deep-water pond where they can safely build their lodges.

The lodges are well-insulated mounds of sticks, rocks and mud. The intricate dwellings have earthen-floored chambers in which the beavers eat and sleep, accessed by multiple underwater entrances. However, in areas where a stream is too large for the beaver to effectively dam its flow, the animals often construct dens in the riverbank, which also have numerous underwater access points.

Long maligned for their active alterations of the environment, beavers today are hailed by many biologists, researchers and ranchers as nature’s premiere architect of healthy, freshwater riparian ecosystems.

“Creeks

developed with beaver in the system, and they will not stay healthy

without them,” Pence said.

“Creeks

developed with beaver in the system, and they will not stay healthy

without them,” Pence said.

Indeed, beavers have a remarkable impact on their surroundings. Dams

create ponds, marshes and bogs, which store water throughout the dry

summer months, but allow ample water to flow onward so a consistent

stream flow is always maintained.

The ponds and lush wetlands improve water quality by filtering sediments and pollutants. The systems slow down and disperse the flow of water, preventing the stream banks from eroding and helping to store nutrient-rich materials that would otherwise be lost through erosion.

Most importantly, beavers act as a “keystone species,” one whose activities are essential for the survival of many other wildlife species. The wetlands they create provide exceptional habitat for raptors, waterfowl, fish and a variety of other fur-bearing mammals, such as otters, coyotes and raccoons. Dragonflies and many other insects lay their eggs in beaver ponds, where their waterborne larvae and nymphs flourish. Fish and their spawn, including trout in Idaho streams, actively feed on the larvae and insects. Moose, elk and deer frequent beaver ponds to drink and feed on willows and other plants adapted to thrive in wetland environments. Because beavers do not harvest all of the trees in their vicinity, a mixture of young and old trees fill in the diverse landscape.

Over long courses of time, beaver ponds become filled with nutrient-rich sediment, prompting the beavers to move on to a new area, while their old home evolves into a rich meadow.

Pence, a longtime employee of the Gooding-based Wood River Resource Conservation and Development Area, a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture through which the region’s Beaver Committee was formed in 1986, said beavers not only maintain flourishing riparian ecosystems, they can be used as a tool to efficiently restore degraded stream areas.

The Beaver Committee over the last 15 years has reintroduced six or seven beavers annually into parts of Blaine and Camas counties, to restore beaver populations and to restore creek ecosystems that were damaged by improper land-management practices. In the last 15 years, some 200 beavers have been moved and planted in various parts of Blaine County, he said.

“Many creeks in the

region have improved because of beaver plantings,” Pence said. “I’m

confident that if beaver were removed from those creeks, the areas would

dry up and degrade again.”

Skinner agreed.

“We definitely get good results of riparian improvement from transplanting,” he said, adding that transplanted beavers sometimes migrate out of a chosen area, or are preyed upon by mountain lions.

While the sustained comeback of beavers in south-central Idaho is lauded by many land managers and environmentalists, the species’ success has fueled some animosity from the ever-expanding population of private landowners.

Lee Garwood, senior conservation officer for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, said beavers have established themselves along most waterways in Blaine County, prompting some displaced animals to move into residential areas.

“If you have

waterfront property in Blaine County, you’re going to have beavers,” he

said.

Garwood said Fish and Game fields dozens of complaints each year that

beavers have cut down ornamental trees or attempted to dam a private

waterway.

“A lot of people’s conflicts with this particular animal comes about from a lack of knowledge,” he said, noting that tree damage by beavers can be prevented with simple measures, such as wrapping the trunk in hardware cloth.

In some instances in

which so-called “problem beavers” persist on private land that is not

considered good beaver habitat, the agency will permit out-of-season

trapping permits, he noted.

Beavers are still legally trapped in Idaho, but state biologists say the

number of active trappers is in decline, particularly in the Blaine

County region. The state permits beaver trapping in the greater Magic

Valley region from November through March, but bans trapping on most

public lands in Blaine County.

Mike Todd, an Idaho Fish and Game biologist who oversees fur-bearing species in the Magic Valley region, said the state issued 558 trapping licenses for fur-bearing species—which include beaver, bobcat, otter, fox and raccoon—during a one-year span from June 1999 to July 2000. Ten years prior in 1989, 1,288 licenses were issued. The number of beavers reported to be taken statewide dropped by more than half in the 10-year period, from 5,459 in 1990 to 2,163 in 2000.

“It’s all determined by the fashion industry,” he said. “New York. Rome. Paris. Places like that. But the demand is not really there now, and it’s not economical to trap when prices are low.”

In

1957, 24,000 beaver were trapped in Idaho, but the demand fell off

sharply in the 1960s. However, the demand for furs again surged in the

1970s and peaked in the 1980s, when the price for a single beaver pelt

hit $28. Demand has again lulled in recent years, and today a pelt would

command little more than $10, considerably less than what it might cost

to trap and skin an animal.

In

1957, 24,000 beaver were trapped in Idaho, but the demand fell off

sharply in the 1960s. However, the demand for furs again surged in the

1970s and peaked in the 1980s, when the price for a single beaver pelt

hit $28. Demand has again lulled in recent years, and today a pelt would

command little more than $10, considerably less than what it might cost

to trap and skin an animal.

Todd said Fish and Game officials once aided in the assault, killing beavers and destroying their dams, but now work to ensure the beaver’s well-being in Idaho’s abundant wilderness.

“It used to be the only good beaver was a dead beaver,” Todd said. “We feel like, anymore, it would be a lot better for people to coexist with these animals.”

Pence concurred.

“If the beaver were a villain, why did the country once look as lush as it did.”