| click here for the |

| front page |

| features |

| stanley, idaho |

| bronc riding |

| broadford riot 1885 |

| fighting fires |

| arts |

| three jewelers |

| custom saddles |

| living |

| kitchen design |

| pilates |

| recreation |

| white water fun |

| sporting clays |

| names of the peaks |

| summer trails |

| summer a to z |

| dining |

| seafood in the mtns |

| calendar |

| summer 2002 |

| listings |

| galleries |

| outfitters & guides |

| fitness |

| tennis |

| golf |

| property mgmnt. |

| lodging |

| dining |

| maps |

| ketchum+sun valley |

| summer trails |

| KART bus map |

| the guide |

| last winter |

| advertising |

| about us |

| copyright |

| Copyright

© 2002 Express Publishing Inc. All Rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form or medium without express written permission of Express Publishing Inc. is strictly prohibited. |

| Produced

& Maintained by Express Publishing, Box 1013, Ketchum, ID 83340-1013 208.726.0719 Voice 208.726.2329 Fax info@svguide.com |

| The Sun Valley Guide is distributed free twice yearly to residents and guests throughout the Sun Valley, Idaho resort area communities. Subscribers to the Idaho Mountain Express will receive the Sun Valley Guide inserted into the paid edition of the newspaper. |

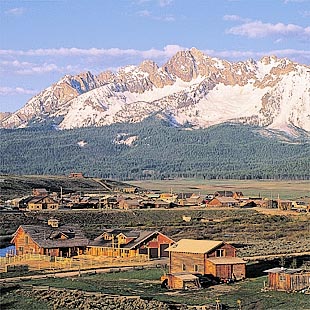

The

Double Life of Stanley

Every

summer, this rugged mountain town blossoms into a mecca for tourists

by Pat Murphy

When air charter service operator Bob Danner speaks of his hometown of 60 years, it’s with affectionate good humor and a touch of mock disparagement.

“Too many people (live) here already,” Danner said, a wink clearly in his voice.

“Too many people (live) here already,” Danner said, a wink clearly in his voice.

“Here” is the city of Stanley, a scattering of homes and small businesses astride the T-shaped junction of State Highways 21 and 75 some 60 miles north of Sun Valley and Ketchum.

The population explosion that concerns Danner is the grand total of 100 people in Stanley proper, double the population of 47 heads just 25 years ago, but far fewer than the headcount in the mid-1860s when gold fever set off a stampede of prospectors to the desolate area.

He quickly and wryly adds, “It’s a nice place to visit, but not to live,” citing with equal humor that during Stanley’s notoriously cold and confining winters residents need to chop firewood furiously to stay warm. And although sub-zero Stanley winters and deep snow are sources of gripes, they’re also grist for grudging hometown pride: Stanley occasionally is celebrated in national news reports as the coldest spot in the Lower 48.

Longtime resident Kathy Cole, who along with her husband operated the rustic, 1931-vintage Sawtooth Hotel before donating it to Albertson College for an off-campus study center, remembers a 1977 December day when the mercury plunged to 63 degrees below zero.

For every outlandish tale of Stanley’s harsh winters, however, dozens of other superlatives are recited by the town’s fiercely proud residents—glowing adjectives of short summers that attract as many as one million visitors into the 300-square-mile Sawtooth Valley. They come for world class outdoor recreation activities or to simply immerse themselves in a quiet tranquillity.

It is a tranquillity little changed since Hudson Bay fur trappers, led by a Scottish teacher Alexander Ross, were the first white men to explore the area in 1824. It was a time when only the Shoshone Indians—called “Sheepeaters” by explorers—roamed the area.

It is a tranquillity little changed since Hudson Bay fur trappers, led by a Scottish teacher Alexander Ross, were the first white men to explore the area in 1824. It was a time when only the Shoshone Indians—called “Sheepeaters” by explorers—roamed the area.

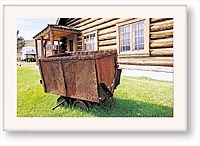

The name Stanley didn’t stick until 1863, when a prospecting expedition led by Capt. John Stanley—the origin of his military title is vague—discovered gold and worked the area. It wasn’t until 1948 that Stanley was incorporated as a city for the inelegant, but highly practical, reason of wanting to sell whiskey legally.

If Stanley’s motivation for incorporating was offbeat, it has yet another singular claim: Stanley is the only incorporated city inside any of America’s federal park and recreation lands.

To locals, there are two Stanleys: the 4-square mile incorporated area along highway 21—curiously known in pre-incorporation days as Dogtown—and the adjoining unincorporated Lower Stanley, once known as Squawtown, which is north of the official Stanley along State Highway 75 and abreast of the north-flowing Salmon River.

The unchartered Lower Stanley, a collection of small motels, outfitter stores and convenience store with a population of perhaps less than 50, and its Upper Stanley neighbor haven’t always enjoyed a serene coexistence. Years ago, a debate arose over where to locate the local post office, which finally was sited in the city of Stanley.

What is it about this winter icebox-cum-summer wonderland that spellbinds hardy residents to remain year-round and lures hundreds of thousands of recreationists to its solitude for a few months each year? And in this age of high-tech gadgets, is life cruel without cell phones and cable TV?

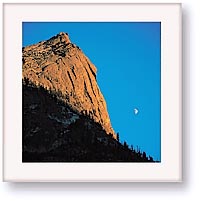

To a person, Stanley residents agree that the isolation appeals to their spirit of freedom, independence and rugged self-reliance in often harsh conditions and mystical beauty that is walled in by four mountain ranges: the imposing but treacherous 10,000-foot-plus Sawtooths, Boulders, White Clouds and Salmon ranges that collectively are often dubbed the “Switzerland of America.”

From the upper reaches of the Smoky Mountains, just on the north side of Galena Summit, a veritable trickle of water gives birth to the lively, winding 420-mile Salmon River—the longest river confined wholly in a single state.

From the upper reaches of the Smoky Mountains, just on the north side of Galena Summit, a veritable trickle of water gives birth to the lively, winding 420-mile Salmon River—the longest river confined wholly in a single state.

Perhaps Henry “Trapper” Fisher, a wilderness character in the finest tradition of the word, is eloquent testimony to the dogged spirit that typifies the Stanley nature: Arriving in Stanley in 1877 in search of furs, Fisher remained through cold winters and primitive conditions until he died in 1950, at 103 years old.

For many businesses, life can be challenging, as virtually all income is confined to the few summer months of hectic tourist activity. Mayor Hilda Floyd resigned this year and left town after deciding to close down her bed and breakfast hotel. The council elected one of its members, Paul Frantellizzi, 42, a three-year resident of Stanley and a businessman, as the new mayor.

In her book, “Stanley-Sawtooth Country,” Esther Yarber described this land of dramatic contrasts and challenges to the human will simply and clearly: “Here nature insists on being met on its own terms … awesome and solemnly beautiful … winters long and bitter cold, summers short and delightful.”

All this grandeur is held in perpetuity for generations yet unborn, set aside by Congress as a tribute to the legacy of Idaho’s late Democratic U.S. Sen. Frank Church, whose wilderness legislation created the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, an almost indescribable collection of 300 mountain lakes; 50 peaks of more than 10,000 feet; headwaters of four major Idaho rivers—the Salmon, also known as “The River of No Return,” the Payette, Boise and Big Wood.

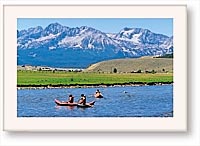

For visitors, Stanley is the jumping off place for an extraordinary choice of adventures—exploring historic nooks and crannies of backwoods where miners and trappers endured harsh conditions or enjoying Mother Nature’s majestic treasures. Forests teem with wildlife species and brilliant blooming summer wildflowers. White water rafting and kayaking, mountain climbing beckon the action-minded. For those with a yen to contemplate beauty at a slower pace, lush woodlands invite hiking and biking and camping, fly fishing, photography, lakes and mountains that can be beheld in awe.

For visitors, Stanley is the jumping off place for an extraordinary choice of adventures—exploring historic nooks and crannies of backwoods where miners and trappers endured harsh conditions or enjoying Mother Nature’s majestic treasures. Forests teem with wildlife species and brilliant blooming summer wildflowers. White water rafting and kayaking, mountain climbing beckon the action-minded. For those with a yen to contemplate beauty at a slower pace, lush woodlands invite hiking and biking and camping, fly fishing, photography, lakes and mountains that can be beheld in awe.

Public access hasn’t always been simple or easy. Highway 75 from the Sun Valley/Ketchum area to Stanley wasn’t fully paved until 1954. What’s more, the last nine miles of Highway 21 from Boise on the west wasn’t paved until 1975, according to Bernice Hartz, a retired teacher at the Sawtooth National Recreation Area’s interpretive center near Ketchum.

The area is a fish and wildlife paradise. Elk, moose, mule deer, fox and coyote are abundant. More elusive but also present are the otter, wolverine, badger, bobcat, black bear, mountain lion and gray wolf. Birds include golden eagle, osprey, raven, magpie, gray jay and the mountain blue bird, Idaho’s state bird. Chinook and sockeye salmon, which gave the river its name, still return from the Pacific Ocean in summer, along with steelhead rainbow trout in spring.

Hard to believe, but settlements up and down the flat floor of the Sawtooth Valley between Galena Pass (elevation 8,701 feet) and Stanley (elevation 6,250 feet) once numbered thousands of miners and their families in the late 1800s and early 1900s. But with mines played out, the outrush shrank the valley’s full-time population to today’s estimated 500 permanent residents, including those in Stanley.

This sense of wide-open spaces and scarcity of people are part of the charm that lures more vacationers to discover the Sawtooth Valley and Stanley. The steady increase in the area’s popularity is regarded watchfully by the U.S. Forest Service, whose handsome log district ranger station overlooking Highway 75 just south of Stanley is a trove of information for tourists.

Stanley District Ranger Lisa Stoeffler says the Forest Service mission “to preserve the character of this whole area” means generations yet to be born will enjoy the area.

Stanley District Ranger Lisa Stoeffler says the Forest Service mission “to preserve the character of this whole area” means generations yet to be born will enjoy the area.

For city folks approaching Stanley on their first visit, one of the first eye-popping experiences during winter might be the sight of large elk feeding on hand-strewn hay alongside the road.

With the arrival of summer, Stanley’s pace and population pick up, as service personnel and guides return. The nightlife blossoms, as saloons with a touch of the Wild West throb with lively nighttime abandon. Residents revive popular local events: the Mountain Mamas Arts and Crafts Show, the Chamber of Commerce Pancake Breakfast, Bow Hunters State Jamboree, kids parade and fireworks display, the Stanley Writers’ Conference, the Quilt Festival.

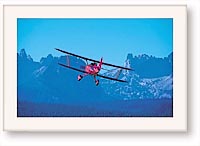

Summer changes life, too, for Bob Danner, a Stanleyite since a few months after being born in Twin Falls in January 1942. Danner resumes operations of his Stanley Air Taxi from the state-owned airport and its 4,300-foot turf runway.

It is a business of hauling rafters and campers into back country airports, working under contract to the Nez Perce Indian tribe tracking wolf packs, delivering groceries to remote summer settlements and flying sightseeing trips.

Danner has three single-engine aircraft: a heavy duty Cessna 206, a souped-up Cessna 182 (which Danner’s wife, Dia Terese, flies for pleasure) and an open-cockpit, circa 1930s Waco UPF-5 biplane.

When winter snows close the airport, Danner moves the Cessna 206 to Hailey, where Danner drives when a flight is ordered by a customer. The other two are stored and maintained in a hangar a few steps from Danner’s home-office.

Between late July and early September, Stanley airport is the state’s busiest backcountry field—as many as 75 aircraft coming and going each day.

Interestingly, the airport once was part of the broad Stanley holdings of the late Nevada casino tycoon and classic car collector, Bill Harrah, whose Stanharrah Corp. sold it to the state of Idaho in October, 2000. As Stanley’s largest single property owner, Stanharrah (a contraction of “Stanley” and “Harrah”) embraces the large Mountain Village complex with motel, restaurant and outfitter store, a major service station and large general store, assessed by Custer County for a total of $7,156,511. Total county, city and special district taxes yield $54,875, of which $19,860 goes to the city of Stanley.

Interestingly, the airport once was part of the broad Stanley holdings of the late Nevada casino tycoon and classic car collector, Bill Harrah, whose Stanharrah Corp. sold it to the state of Idaho in October, 2000. As Stanley’s largest single property owner, Stanharrah (a contraction of “Stanley” and “Harrah”) embraces the large Mountain Village complex with motel, restaurant and outfitter store, a major service station and large general store, assessed by Custer County for a total of $7,156,511. Total county, city and special district taxes yield $54,875, of which $19,860 goes to the city of Stanley.

When two Harrah sons, John and Tony, reach their 40s, they’ll inherit the property. Therein lies a cliffhanger: Will they sell the property, continue as landlords, or develop holdings further? A collective civic breath is being held by the town waiting for an answer.

Stanley Chamber of Commerce marketing consultant, Greg Edson, of Twin Falls, says the Harrah sons decision will be crucial in the future of Stanley, a community that he describes as “blossoming” without booming. With only 168 acres in the area available for development, and land prices soaring to $100,000 for a half acre, the future of the Harrah properties will impact the community.

Until he died, Harrah had visions of developing the area’s hot water springs for therapeutic and recreational uses, an RV park and more retail establishments, Edson explained. Notwithstanding the eventual fate of the Harrah properties, Edson anticipates this: more accommodations for “family” vacationers in Stanley and construction of large second homes for wealthy absentee owners. Edson is especially high on joint study with the state on the feasibility of an all-events center to house an array of recreational, educational and civic activities.

Danner says Harrah was a generous man who loved Stanley’s ambiance, and had only modest goals for his holdings. “He’d bring friends here—like Sammy Davis Jr., Bill Cosby, Jim Nabors, Glen Campbell—for hurried vacations, Danner said.

With or without such a famed and moneyed property owner, Stanley’s stubbornly self-reliant residents have built an amazing array of pieces of the civic infrastructure through pure volunteerism.

Kathy Cole, who moved to Stanley in 1974, and her husband, Steve, spearheaded the founding of the fire department after a sawmill fire had to be fought with a primitive bucket brigade. Harrah donated the first fire engine. The Coles also created the Stanley Writers’ Conference.

Julie Meissner, a seasoned outfitter and guide who settled in Stanley 20 years ago and spends winters doing what many in the outfitter industry do during those long cold months—wrapping fishing rods and tying as many as 500 fishing flies—is one of a dozen volunteer emergency medical technicians on call for Stanley’s Salmon River Emergency Clinic. She thinks nothing of having to ski out of her home to the nearest road in the winter.

With such a small population and with so many demands, it’s not unusual to find Stanley residents each involved in two or three or more volunteer civic projects.

Aside from civic high-mindedness this pull-together attitude breeds, it also forges such neighborly bonding that crime is virtually non-existent. Thus, Stanley’s need for only a one-man, part-time police force, Phil Enright, and the presence of the area’s Custer County deputy sheriff Spencer Uhl.

The town is not without issues.

The Sawtooth Community Winter Recreation Partnership tackled and solved the difficult problem of how to balance the needs of cross country skiers and snowmobilers trying to share the same recreation areas.

Although the town boasts a K-8 elementary school with 40 students, it lacks a public high school. In the 2001-2002 school year, Stanley had seven high school age students: three who remained in Stanley for private schooling, but four who endured the rigors of 12-hour school days and a 120-mile daily round-trip to Challis to attend a high school. A local committee is trying to persuade the state Board of Education to fund a high school in Stanley.

Wildlife issues are predictably divisive: pro and con forces argue whether elk should be fed by locals during the winter and whether wolves should be welcome in the area.

One issue does seem to bring together the entire town: the perennial dilemma of trying to keep the road to Boise, State Highway 21, open all winter, despite rock slides and avalanches.

Julie Meissner senses a deeper unifying theme, the reason her town attracts both hardy residents and wide-eyed visitors: “Many of the people we see here,” she says, perhaps reflecting on her own 1981 decision to sink her roots in Stanley, “are looking for places with ‘values’.” •

sidebar:

Redfish Lake

By Pat Murphy

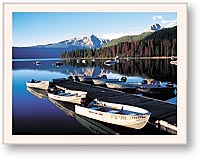

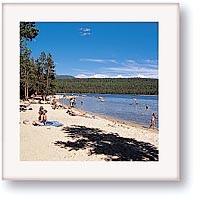

Known as “the jewel of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area,” Redfish Lake, and nearby Little Redfish Lake, has it all for summer vacationers who want to hang out in one place.

Just 5 miles south of Stanley and then 2 miles off State Highway 75, Redfish is a picturesque 5-mile-long, 300-foot deep glacial lake at the base of an array of mountains—the highest, Mount Heyburn, is 10,229 feet—where prehistoric hunters camped and fished 9,500 years ago.

Just 5 miles south of Stanley and then 2 miles off State Highway 75, Redfish is a picturesque 5-mile-long, 300-foot deep glacial lake at the base of an array of mountains—the highest, Mount Heyburn, is 10,229 feet—where prehistoric hunters camped and fished 9,500 years ago.

Since 1929, the Redfish Lake Lodge, which is operated under license of the U.S. Forest Service, has been accommodating visitors—as campers, RV users and guests in a wide selection of cabins scattered along the shores of Redfish.

Activities at Redfish (elevation 6,547 feet) cover the gamut—mountain climbing, horseback riding, swimming, photography, painting, boating, volleyball, horseshoes, a self-guided tour of Fishhook Creek Nature Trail, hiking, fishing and biking.

One scenic climbing area is a valley across a high ridge from Redfish known as Shangri-La, reminiscent of the ageless Utopian hideaway fantasized in the 1937 movie “Lost Horizon.”

One scenic climbing area is a valley across a high ridge from Redfish known as Shangri-La, reminiscent of the ageless Utopian hideaway fantasized in the 1937 movie “Lost Horizon.”

For those wanting to widen their choice of vacation recreation, the area boasts some of the finest river rafting and kayaking, scenic aerial flights, scenic drives, nearby ghost towns and hot springs.

Redfish also has become the popular setting for weddings and receptions during the summer months.

One of the intriguing footnotes to the history of Redfish Lake was a planned fish cannery for the lakeside during the 1800s when thousands of gold prospectors and miners and their families settled the Sawtooth Valley area. Redfish Lake at the time was so filled with sockeye salmon that a cannery was considered commercially feasible. But the mines played out, settlers left the area and the cannery was never built. •

One of the intriguing footnotes to the history of Redfish Lake was a planned fish cannery for the lakeside during the 1800s when thousands of gold prospectors and miners and their families settled the Sawtooth Valley area. Redfish Lake at the time was so filled with sockeye salmon that a cannery was considered commercially feasible. But the mines played out, settlers left the area and the cannery was never built. •